And if you like Bluegrass, Blues, 'roots' and Woodie Guthrie inspired music, you'll probably want the game, just for the OST (official soundtrack).

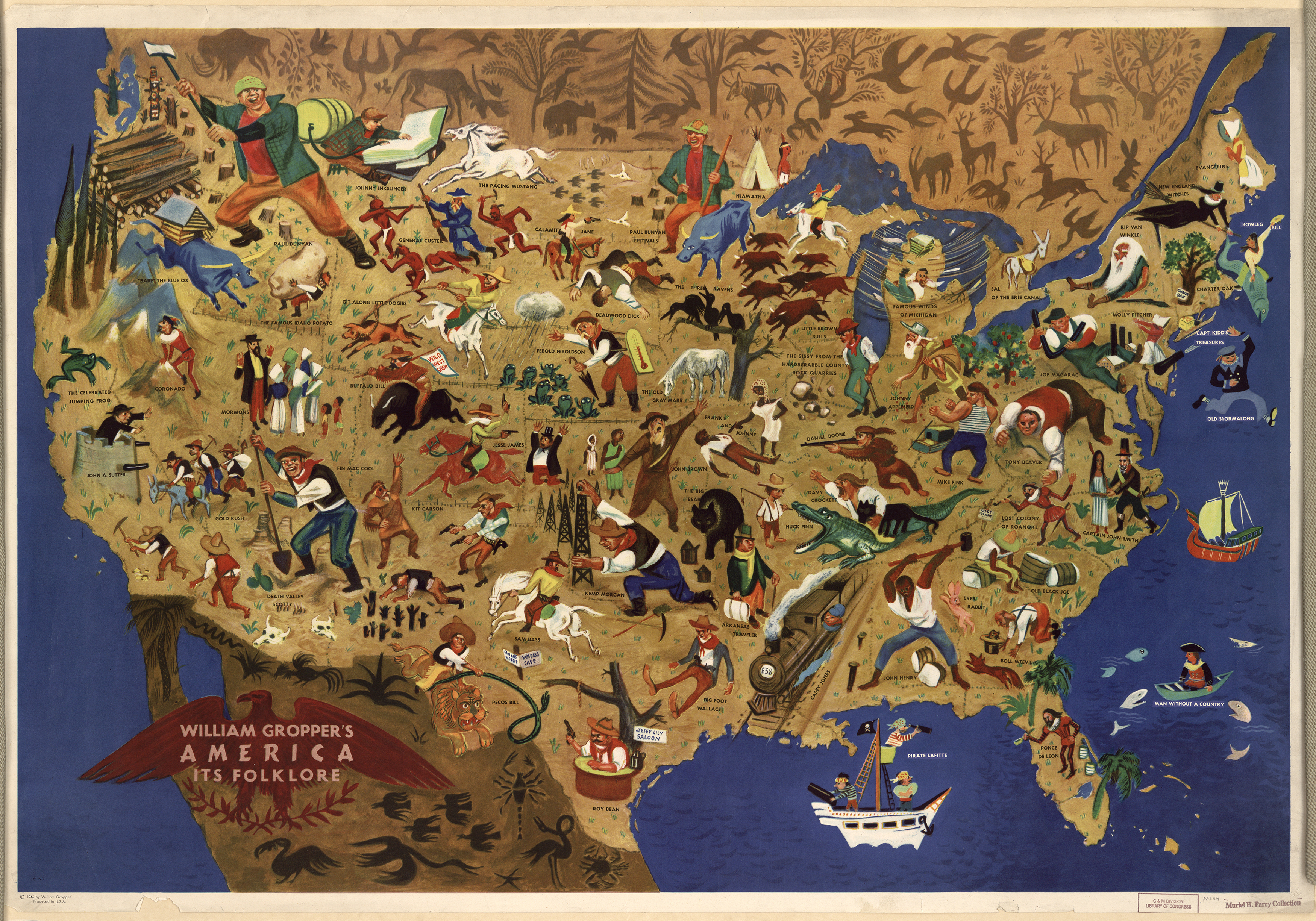

You play a traveler wandering through the United States - and through a century of history and the Great Depression era - to meet a variety of people, each with their own stories to tell. Presented as a "bleak American folktale", the currency is stories you collect on your travels, and that you tell around the campfires. A fantastical undercurrent runs through the game, with anamorphic people and surreal encounters being a common occurrence. The map is a gorgeous illustrative overlay filled with trees, highways, and campfires that glow in the night. (We've included some development art in this post.)

Envisioned as "a bleak American folktale," Where The Water Tastes Like Wine is a gripping and morbid adventure game that lets players explore the landscape of the country, using stories they find along the way as currency. The brief snippet we played showcased gorgeous visuals, a lovely soundtrack, and fantastic short stories that were both moving and macabre. – (Javy Gwaltney, Gameinformer)

Sounds pretty interesting, right? Well it gets better. Turns out there are multiple characters to be found all over this America, both with folktales and personal stories to tell, and the developers employed a wide variety of excellent writers to be the 'voices' for each one. (You can read their impressive bios HERE.) This means the telling is done differently by each character and the flavor of the stories and the person change, just like they do when collecting stories in life.

Take a look at the trailer:

We get more insight into the game and the folktale aspect via a few different interviews. Excerpts are below with the source credited after each extract:

"The art suggests that there's more going on in the world than what we necessarily see," Nordhagen told IGN. "Every once in a while we see through the cracks in the world and get a peek at other realities. It's recognizably America, though - poker and trains, the Southwestern desert mesas, and something that suggests the colorful and idyllic farm produce labels of the beginning of the 20th century. It's the sort of America that might live in tall tales, in blues, folk, and bluegrass songs, and travelers' stories." (IGN)

"The title comes from a folk song, or, more accurately, lots of different folk songs," Nordhagen explained. "American folk culture is one of collaboration, sharing songs and stories but giving them your personal twist. It comes from many different cultures - the European settlers, the slaves that were forced to live here, the workers who have traveled here in search of opportunity, and of course the people actually native to this land."

"Many of the songs, stories, and poems deal with hardship, especially in the blues genre, and many are about traveling the country," he added, citing such influences as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Grapes of Wrath and On the Road. "There are many stories of other American wanderers that rarely get told - the spread of African Americans from the south, the movement of migratory farm workers, or the forced marches of native people. Where the Water Tastes Like Wine wants to capture the feeling of those songs, poems, stories, and wanderings in a game." (eurogamer)

Heroic travelers aren't the only people featured in the game. "Most of the romantic road stories out there are white males traveling and having adventures," he said. "That is a freedom only available to those people, but a lot of travelers don't have that freedom and I want to tell stories of people who have been displaced." (polygon)Here are some screen shots:

Sounds ambitious - and wonderful! Right now the release date is yet to be set but this will be available for Steam, PC/Mac later in the year, and other platforms XBoxOne and PS4 sometime later after that. We're thinking of preordering!

To finish, here's an interview with the creator (known for his critically acclaimed previous game Gone Home) at the convention SXSW 2017 (South By South West) in which you can hear a little more about how this game came to be, and see some more of the art in motion and a little gameplay. It begins with a typical upbeat 'gamer' intro, but quickly gets into the meat of the interview. Totally worth watching we promise. Enjoy!

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523678/thenortheast.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523682/thesoutheast.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523684/themidwest.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523688/thesouthwest.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523690/thewest.0.jpg)