|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

Note: My apologies I didn't get this up sooner to join in the discussion as it was happening, never having completed my initial draft. I've adapted my post to reflect comments already published as a result.

Unfortunately my posting may be rather more erratic than usual these few weeks with some "life stuff" on my end but I will do my best to post as often as I can.

(And no matter how many times I fix it the formatting keeps changing! I've contacted Blogger about it but have had no answers as to what to do about it yet.)

(And no matter how many times I fix it the formatting keeps changing! I've contacted Blogger about it but have had no answers as to what to do about it yet.)

You've probably read Heidi's post on Professor Maria Tatar's column in The New Yorker, discussing the "500 rediscovered fairy tales" of Franz Xaver von Schönwerth. If you didn't click through and read The New Yorker piece on March 16th: "CINDERFELLAS: THE LONG-LOST FAIRY TALES Posted by Maria Tatar", I highly recommend it.

There is also another post you should be aware of by The Sussex Center for Folklore, Fairy Tales and Fantasy, who were given permission to publish a cautionary note on the tales rediscovery by Professor Jack Zipes. You can find the post, "AN EXTRAORDINARY NEW FIND AND JACK ZIPES ON THE 500 NEW FAIRY TALES" HERE.

Since the whole rediscovery has been touted as such an important "event" in the world of fairy tales, and since I've done a lot of reading of various posts on the subject, including a lot of comments and followed a lot of links, I wanted to add my own two cents to back up what Heidi and the rest of the fairy tale scholars are saying right now and to mention the Cinderfella issue too.

To summarize (I'm going to do my best to keep each point short with just a few notes on each):

1) The 500 "new" tales are not new.

a) Of the 500 tales quite a number are versions of tales we already know and love - just in raw, incomplete (and, from what I've read) barely readable form. (Yeah... I know.)

b) The tales are barely able to be classified as "rediscovered" either since it turns out that quite a number of them existed ON THE INTERNET in some form already - just not in English. (I know!)

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

a) As far as I can understand it, the Schönwerth tales are straight oral dictations and don't include any cultural observation and research (which would include direct transcriptions of oral tales as told to the writer, along with notes to help in later understanding of what was recorded) nor are they immediately readable by the average person (ie. the reaction would likely be: "What the..?!").

b) The Grimm Brothers get a lot of flack for having used their writing skills to shape and mold the tales to their preferences. While some of that criticism can be justified (especially from our perspective in history) there's a lot to be said for using artistic sensibilities when relating or retelling a tale. When you think about it, aren't you glad the Grimm collections can be read beginning to end without skipping over um's and ah's and stopping to jump back and forward to try and make sense of a story? Can you imagine trying to read something that included common oral goofs such as "..hang on, that happened before she picked up the egg, so I guess she must have pulled out the other thing at the river..."? (If you don't know what I'm talking about with that example, well, that's kind of my point.)

c) By their nature, fairy tales have an oral heritage that changes with the teller, the listener*, the period, the situation and culture too. Written down fairy tales have to do the same thing - otherwise the story can be - literally - lost in the (lack of) translation. There's a reason Editors are so highly regarded and good ones are sought after. Storytelling is an art form. Writing down an oral art form has a number of challenges if it's to convey any sense of that art and bridge the gap between listener and reader audiences. Just like a movie writer/director adapting a book to screen, an artistic sense is key in bringing the tales to a new medium and audience. No matter how good the book is, if the director doesn't understand the medium of story telling via film and how to put the "magic" of the book's story into moving images, the movie will likely flop. Not only that, it can also have a negative affect on the original source. A filmmaker has to make a new creation out of the old that continues to give to the story. So too for any tales changing form (in this case from oral to written). Extra "skillz" needed!

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

"Schönwerth’s tales have a compositional fierceness and energy rarely seen in stories gathered by the Brothers Grimm or Charles Perrault...

The stories remain untouched by literary sensibilities. No throat-clearing for Schönwerth, who begins in medias res, with “A princess was ill” or “A prince was lost in the woods,” rather than “Once upon a time…”

Though he was inspired by the Grimms, Schönwerth was even more interested than they were in documenting the oral traditions of Bavaria. He hoped to preserve remnants of a pagan past and to consolidate national identity by capturing in print rapidly fading cultural traditions, legends, and customs. This explains the rough-hewn quality of his tales. Oral narratives famously neglect psychology for plot, and these tales move with warp speed out of the castle and into the woods, generating multiple encounters with ogres, dragons, witches, and other villains, leaving almost no room for expressive asides or details explaining how or why things happen. The driving question is always “And then …?”

This is of great value to new storytellers but means, essentially, there is quite a bit of work to be done before these stories can enter a storybook for publication or to be passed down through generations. In other words, before a public can appreciate and "access" them (in the tale sense of the word) they need a bit of work. Think basic ingredients without herbs, spices and a cook's attention for taste! In tales it's the details that often capture attention and imagination... eg from Grimm's Little Snow White, emphasis in bold is mine: Three drops of blood fell into the snow. The red on the white looked so beautiful that she thought to herself, "If only I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood in this frame.") Our scholars have their work cut out for them.

e) Since we already have a love and understanding of various Red Riding Hood, Snow White, Rapunzel and Cinderella's via Grimms and Perrault, among others, it would be interesting to see what light these raw versions of the same tale might shed on them. If they bring a new understanding of tale, history, culture and more then we have a valuable find indeed. If it brings only a scratching of heads then it might be indication that the rest of the tales should be considered with the same number of grains of salt. (Note: this is my speculation only. I'm not a translator. I cannot make any useful sense of what I've seen in the German texts online beyond direct - and my very amateur - translation of the words. I'm just following logic here.)

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

...I can point to some brilliant German collections by Theodor Vernaleken, Johann Wilhelm Wolf, Ignaz and Joseph Zingerele, Heinrich Pröhle, Josef Haltrich, Christian Schneller, Karl Haupt, Hermann Knust, Carl and Theodor Colshorn, etc. etc. and even more brilliant French collections by François-Marie Luzel, Paul Sébillot, Emmanuel Cosquin, Jean-François Bladé, Henry Carnoy, etc. etc. that contain tales fastidiously recorded by these folklorists, who translated them from dialect versions. They also include raw dialect versions with their translations. You can also see this in my and Joseph Russo’s translation of Giuseppe Pitrè’s Sicilian tales, The Collected Sicilian Folk and Fairy Tales of Giuseppe Pitrè (2008). Pitrè’s tales are also raw like Schoenwerth’s, but more fascinating because his ear was better and he wrote them down in dialect. Indeed, we have not yet translated the best European folk-tale collections into English and given them their due recognition, and I would not put Schönwerth’s tales at the top of my list of collections that need more study. We must ask what the significance of Schönwerth’s collection is within the development of oral folk tales during the nineteenth century, and it is too early to do this, whereas some of the other collections are clearly important for understanding how and why the tales were disseminated.a) As you can see from the quote, interestingly, many of these are "raw" tales too but contain additional notes and writings that may assist in translating the tales and adapting them for modern day readability. This is not to take away from the value of the find necessarily, but to say this should perhaps point the way to more of the same and some possibly even more exciting treasures awaiting our attention.

b) We have a lot of tale-catching (up) to do!

c) And translators should be better valued than they are.

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

Our own culture, under the spell of Grimm and Perrault, has favored fairy tales starring girls rather than boys, princesses rather than princes. But Schönwerth’s stories show us that once upon a time, Cinderfellas evidently suffered right alongside Cinderellas, and handsome young men fell into slumbers nearly as deep as Briar Rose’s hundred-year nap. Just as girls became domestic drudges and suffered under the curse of evil mothers and stepmothers, boys, too, served out terms as gardeners and servants, sometimes banished into the woods by hostile fathers. Like Snow White, they had to plead with a hunter for their lives. And they are as good as they are beautiful—Schönwerth uses the German term “schön,” or beautiful, for both male and female protagonists.

Why did we lose all those male counterparts to Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and the girl who becomes the wife of the Frog King? Boy heroes clearly had a hard time surviving the nineteenth-century migration of fairy tales from the communal hearth into the nursery...Personally, I'm not convinced that mothers and nursery maids are the main reason boys didn't suffer as much as the girls in our canon tales. They survived just fine before the mid-1800's in Europe and through and after in cultures such as Russian, Chinese, Norwegian, Indian and many more. I do think the Grimm's editing and the availability of their tales in print form had a lot to do with this narrowing of focus though. To continue the movie metaphor, it's like blockbusters versus independent films. Which do you think has the greatest chance of surviving history to be studied in the future? Considering the power and dollars in "princess marketing", do you think in a few hundred years that The Walt Disney Company will be remembered for the boys club it's actually known to be?

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

Regarding the Grimm's editing (a.k.a. censorship), again, this isn't "new" news but Schönwerth being a fellow countryman of the Grimm Brothers does help shed light on just how much editing the brothers did for the sake of boosting a paternal national identity and, specifically, not exposing the males in the stories to the same vulnerabilities as the females, something which seemed to be very important politically at the time.

Note: I'm not an expert - there are many books on the Brothers Grimm that can explain this far more accurately and succinctly! Please go check them out.

What I'm really chiming in to say is that, despite this no-new-news news, I'm still excited about three things:

1) We really do have a wealth of tales yet to explore - and Schönwerth's Turnip Princess should be easily equaled - and has a good chance of being surpassed in terms of story quality - among the myriad yet to be studied.2) There is a wealth of "Cinderfella" tales related to those we're already familiar with (from a Western canon point of view) that mothers like me cannot wait to see put together as collections to share with our sons. Schönwerth's volumes may help dust those off for the public and help bring them back into circulation. (I would dearly love more fairy tales for boys books, beyond myths and dragons, to share with my son!)3) Anything that gets the public excited about fairy tales and what they may have to offer is, in my opinion, of value!

|

| Sergey Tyukanov |

I'm actually quite surprised at the enthusiasm I've seen OUTSIDE of fairy tale circles. (See this Metafilter thread HERE as an example and note the many, many comments). It's fascinating to see what people are hoping will be "found"/uncovered. It says a lot about how fairy tales in general and as a part of our history and heritage, are considered: as precious. It helps explain why, when times are bleak and in times of wide spread depression and tragedy, fairy tales become popular again and why we feel that within these tales we will find hope and a way through the woods.

* The listener, yes! Whom the tales are told to - the age, the situation, the cultural norms etc etc - seems to be overlooked much of the time only to become a sticking point later when everything gets lumped together. It's like someone in the future saying everyone went to see all the movies playing at the local theater in 2012. It just doesn't work that way. Who told the tales to whom can be somewhat paralleled to this.

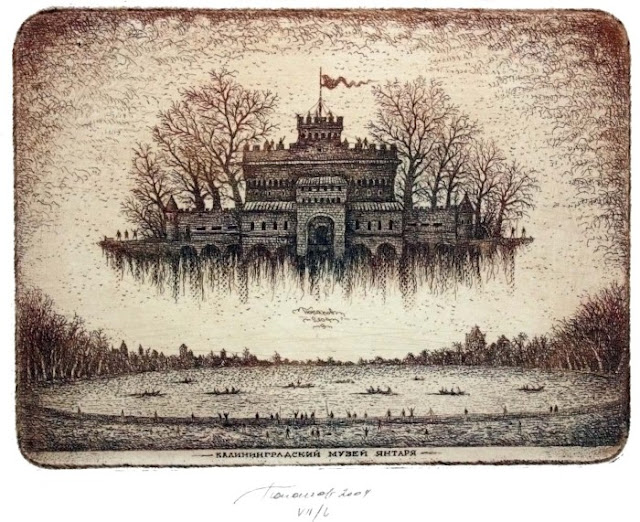

Note: All the amazing etchings featured in the post today are by Sergey Tyukanov. And yes - they very much reminded me of some fairy tales I've read for boys! I think some of these would go very well in a volume of tales for boys. You can find more of his etching work HERE. His wonderful website with work in all media and colors is HERE (including some really different and interesting Alice In Wonderland paintings - honestly, you've never seen anything quite like this version of Alice!) and his blog, in Spanish, is HERE.

Both Professor Zipes and Maria Tatar are now working in close collaboration with Erika Eichenseer to see how to bring these tales to a wider audience. So Zipes' post in Sussex is outdated!

ReplyDeleteI am a Jungian Analyst in Colorado, and for the past several months I have been working on interpretations of some tales from another translation of some of Schönwerth's collection. This volume is translated by M. Charlotte Wolf (Dover publication 2014) and is titled, "Original Bavarian Folktales: A Schönwerth Selection." There are 150 tales in this dual-language edition. In the recent hoopla about the translation coming out by Maria Tatar, this volume published last year seems to never be mentioned. I am happy to see that Tatar is translating more of the tales, and I do love reading and working with the stories from Schönwerth's collection, but I just want to say that the translations of Wolf are really finely done and deserve attention! In her introduction, she gives a very thorough account of the manuscripts ("thousands of handwritten pages in 30 ungainly boxes"), their discovery in 2010, the publication of "Prince Dung Beetle," etc. The volume is worth looking at, for those of you who want to have the whole story!

ReplyDeleteAs for the rawness, I do find Schönwerth's collections to be very raw and exciting to work with. As a psychological interpreter, I find the archetypal images to be amazingly close to the bone, so to speak, and I have been gaining so much from the work I am doing with these tales!

It is wonderful to read that Zipes and others are working on other translations of other European collections. We will all benefit from these, as well as from the newly rediscovered tales of Schönwerth. We don't need to diminish the worth of one collection in order to elevate the worth of the others. There is plenty of room for all to flourish, and I for one am excited at the attention that these tales are receiving. What an enriching time we live in, to have such material with which to work! I am grateful for all the scholars who are doing this work, and want them to know that many of us truly value their endeavors!