|

| (William Gropper) |

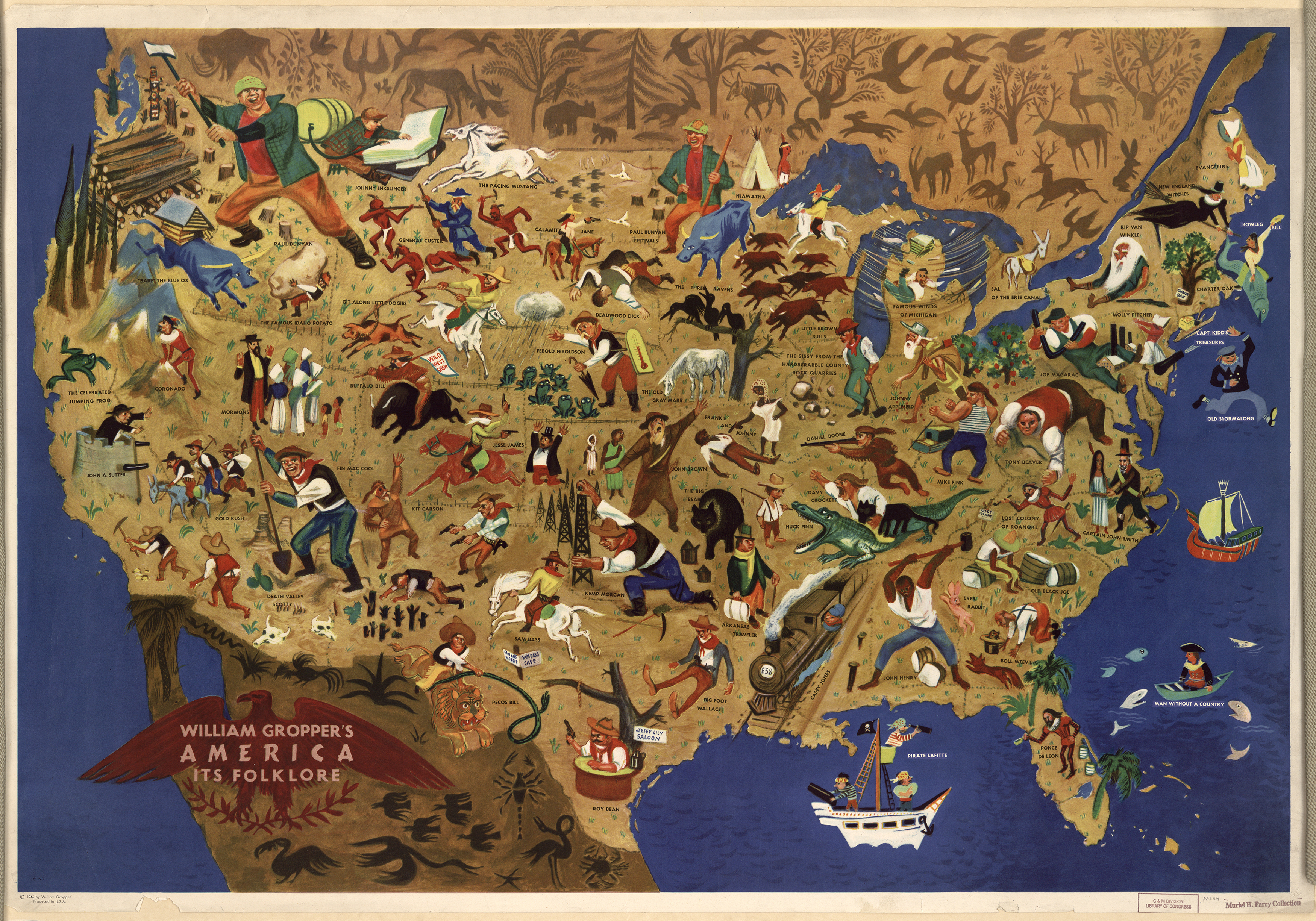

Note: This post was reprinted in full with permission by Phil Edwards. The map is public domain care of the Library of Congress (so go use it if you need to!). The original post is HERE at Vox.

I also wanted to mention that you'll see most of these characters are specific folk heroes and not really fairy tales or fairy tale characters. In fact, that's one of the really interesting things about this map. Each of the names below the region is linked to an expanded explanation (usually Wikipedia) so if you were ever curious, here's your key to begin your study. (I've put some thought on this in the following post).

All of America's folk heroes, in one map

by Phil Edwards

This 1946 map, made by William Gropper, shows all of America's most famous folklore and myths in one gorgeous image. It's not comprehensive, but it's still a fascinating look at the myths that made America, highlighting real people who reached folkloric status as well as those who were invented in stories and song.

You can hover to zoom (zoom function only available at the original post) or see a larger version of the map here. Every region's folk heroes are identified below. Your state probably has a hero — and it may be one you didn't know about already.

The Northeast

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523678/thenortheast.0.jpg)

William Gropper's American Folklore Map. (Library of Congress)

Evangeline (Maine): Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem immortalized the tale of this Acadian girl searching for her lost love.

New England Witches (Massachusetts): The Salem witch trials, from 1692 to 1693, saw the trial and execution of 20 people for witchcraft.

Bowleg Bill (Massachusetts): This Wyoming ranch hand ended up in Massachusetts, where he rode on tuna fish and whales. The tale is found in a popular book published in 1938.

Rip Van Winkle (New York): Washington Irving's 1819 story of the sleepy Van Winkle was set in the Catskill Mountains.

Captain Kidd's Treasures (New York): Pirate William Kid hid some of his treasure on Gardiners Island, a small island just off Long Island.

Sal of the Erie Canal (New York): Featured in the song "Low Bridge," Sal the mule is symbolic of the mules that helped build New York cities such as Utica and Buffalo.

Charter Oak (Connecticut): This tree was famous for supposedly holding Connecticut's Royal Charter of 1662, until it fell in a storm in 1856. It appears on the state quarter.

Old Stormalong (Massachusetts): Alfred Bulltop Stormalong was a giant sailor who cruised New England, fighting the Kraken. He's often called "Old Stormy."

Molly Pitcher (New Jersey): Born in New Jersey, Molly Pitcher (a.k.a. Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley) became legendary for carrying water to soldiers during the Revolutionary War.

Joe Magarac (Pennsylvania): This folk hero was a Pittsburgh steelworker who first appeared in print in 1931. In some depictions, he is actually made of steel.

Famous Winds of Michigan (Michigan): Less folklore than weather phenomenon, this refers to the winds that occur off Lake Michigan.

Johnny Appleseed (West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois): Appleseed, a.k.a. John Chapman, legendarily planted apple trees across the United States. Some claim his apples were used for hard cider.

Tony Beaver (West Virginia): A woodsman from Eel River, he is occasionally called a cousin of Paul Bunyan and is known for his passion for griddle skating. (For those who've forgotten, that involves skating on a griddle, usually with butter-greased feet or bacon shoes.)

Mike Fink (Pennsylvania and Ohio): This semi-mythical man was a tough fighter and boatman. He enjoyed practical jokes, shooting cups of whiskey off his friends' heads, and being strong.

Daniel Boone (Kentucky): Most closely associated with Kentucky, Boone was an explorer who also served in the Virginia General Assembly. Like Davy Crockett later on, Boone's legendary exploits overshadowed his real ones.

The Sissy From the Hardscrabble County Rock Quarries (Indiana): This tale has a simple moral: compared with the tough men who work the quarries, a man who rides panthers and uses a rattlesnake as a whip is a wimp.

The Southeast

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523682/thesoutheast.0.jpg)

William Gropper's American Folklore Map. (Library of Congress)

Captain John Smith (Virginia): The English colonist who led the Virginia colony in Jamestown became legendary for his leadership and the tales of his interactions with Pocahontas.

Lost Colony of Roanoke (North Carolina): The lost colony of Roanoke was located in modern North Carolina. The disappearance of its colonists remains a mystery.

Old Black Joe (South Carolina): Stephen Foster wrote a song about the slave Old Black Joe. Though Joe is not associated with a specific state, the map places him in the Southeast. The song gained a second life when Al Jolson performed it in the movie Swanee River.

Brer Rabbit (Georgia): Popular throughout the South, Brer Rabbit succeeds by tricking his adversaries. The cunning rabbit appears in some form in both African and Cherokee tales.

Boll Weevil (South Carolina): The plague of the South, the boll weevil preyed on the vulnerable cotton crop and was immortalized in many popular songs.

John Henry (Alabama): The legendary steel-driving man is mentioned in several folk songs and tales. He supposedly died when battling a steam-powered engine. Legends place him in West Virginia, Virginia, or, as on this map, in Coosa Mountain Tunnel in Alabama.

Man Without a Country (Off the coast): Edward Everett Hale's story about Philip Nolan is an allegory about an Army lieutenant who renounced his country during a treason trial and was forced to live at sea.

Ponce de León (Florida): Juan Ponce de León was a Spanish explorer who served as the first governor of Puerto Rico, but he probably appears on a folklore map due to his search for the fountain of youth.

Pirate Lafitte (Gulf of Mexico/Louisiana): Pirate Jean Lafitte operated in the Gulf of Mexico and had a warehouse in New Orleans. He was both a smuggler and a pirate.

Casey Jones (Tennessee/Mississippi): This real engineer from Tennessee famously guided the Cannonball Express, which collided with a freight train in Vaughan, Mississippi. Jones' attempts to stop the train made him a legend.

Huck Finn (Mississippi): Mark Twain's famous character lived in the antebellum South and rode along the Mississippi River with his friend, the slave Jim.

Davy Crockett (Tennessee): Both folk hero and real politician, Davy Crockett represented Tennessee in the House of Representatives, explored the frontier, and died at the Alamo. Later, more mythical acts were attributed to him (like jumping on alligators).

Arkansas Traveler/Arkansaw Bear (Arkansas): The state historical song of Arkansas, "Arkansas Traveler" tells of how a local welcomed a lost city traveler. "Arkansaw Bear" is the tale of a boy named Bosephus who met a bear, Horatio, who could talk and play a fiddle. The two became fast friends.

The Midwest

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523684/themidwest.0.jpg)

William Gropper's American Folklore Map. (Library of Congress)

Little Brown Bulls (Wisconsin): This traditional song of Wisconsin lumberjacks details logging along the river. The central story is a contest between some "big spotted steers" and "little brown bulls" to see which could haul the most wood.

Hiawatha (Undefined): The prehistoric Native American leader is usually placed somewhere in New York, though this map puts him in the Midwest. He's a famous symbol for his leadership of the Iroquois confederacy.

Paul Bunyan Festivals (Minnesota): The legendary lumberjack has a home throughout the Midwest, but Minnesota might have the strongest claim on him and his trusty friend, Babe the Blue Ox. Bunyan first appeared in print in a 1916 promotional pamphlet for the Red River Lumber Company.

The Three Ravens (the Midwest): This version of an English ballad tells the story of three ravens who saw a slain knight. (In the Midwestern United States, the knight is occasionally replaced with a horse.)

The Old Gray Mare (the Midwest): This folk song tells the story of an aging mare or mule. Some sources place the song in New Jersey, others credit Stephen Foster, and still others say it comes from a campaign song.

Deadwood Dick (South Dakota): Popularized in dime novels by Edward Lytton Wheeler, the character became a symbol of the infamous cowboy town of Deadwood, and many real cowboys used the name. He's also a pseudonym for African-American cowboy Nat Love.

Calamity Jane (South Dakota): Frontierswoman and fighter Martha Jane Canary became a folk hero for her strong personality.

Febold Feboldson (Nebraska): The Swedish plainsman and cloudbuster was also a farmer and frontiersman who pioneered in the Old West.

General Custer (Montana): The Civil War general hailed from Ohio and was killed at Little Bighorn, Montana. "Custer's Last Stand" remains an infamous battle in American history.

The Pacing White Mustang (The West): Emblematic of the American West as a whole, the pacing white mustang represents the wandering of the West. Described by Washington Irving in 1832, the mustang first appeared in Oklahoma as a near apparition with a wandering soul, too fast to be caught.

Buffalo Bill (Kansas): An infamous figure in the Wild West, Buffalo Bill rode in the Pony Express, fought in the Civil War, and explored the frontier. He began touring in 1883, in a show that burnished his legend as a cowboy.

Git Along Little Dogies (Midwest and West): A traditional cowboy ballad, the song refers to motherless calves and the cowboy's call while herding them.

The Southwest

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523688/thesouthwest.0.jpg)

William Gropper's American Folklore Map. (Library of Congress)

Big Foot Wallace (Texas): A ranger famous for his exploits in early Texas, William A. A. Wallace fought Native Americans and Mexicans. Over time, his adventures became more legendary.

Frankie and Johnny (Missouri): The story of feuding lovers was most famously inspired by a murder in St. Louis, when a 22-year-old woman shot her 17-year-old lover. It became famous through the folk song of the same name.

John Brown (Kansas): John Brown is more a figure of history than folklore, but his raid on Harpers Ferry became a legendary moment in American history. The famous abolitionist was later executed.

Jesse James (Missouri): From Missouri, James was the Old West's most infamous outlaw and a celebrity even when alive. His death at the hands of Robert Fort secured his place in American folklore.

Kemp Morgan (Oklahoma/Texas): The Paul Bunyan of the oil fields, he could smell oil underground and drill for it more effectively than any normal man.

Sam Bass (Texas): This train robber and outlaw was shot in 1878 when scouting a train robbery. He died the next day and became one of a few infamous stagecoach robbers.

Pecos Bill (Texas): The most iconic fake cowboy, Pecos Bill appeared in print in the short stories of Edward S. O'Reilly. He rode a mountain lion and lassoed a twister, among other exploits.

Kit Carson (Colorado): The frontiersman roved the mountains of Colorado and became a legendary guide in his lifetime thanks to his help guiding explorer John C. Frémont. Carson later took part in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, and was involved in many conflicts with Native Americans in the West.

Fin Mac Cool (Texas): An Irish hunter and warrior whose original name was Fionn mac Cumhaill, Fin Mac Cool appears on this map in Texas. A Paul Bunyan figure in Ireland, he may appear in a localized incarnation on the map.

Roy Bean (Texas): This saloon keeper/judge supposedly held court in a saloon along the Rio Grande. He became infamous as a hanging judge (despite little evidence that he did so much in real life).

Death Valley Scotty (California): Walter Edward Perry Scott became known by this name for his many gold-mining scams and his notable mansion in Death Valley, California.

The West

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3523690/thewest.0.jpg)

William Gropper's American Folklore Map. (Library of Congress)

Babe the Blue Ox and Paul Bunyan (the West): Though Bunyan is best associated with Minnesota, he's depicted here wandering across the Pacific Northwest, where numerous logging opportunities would be available.

Johnny Inkslinger (the West): Like Bunyan, Johnny Inkslinger probably belongs in Minnesota or Wisconsin. Still, his unusual story is worth a mention: he was Paul Bunyan's timekeeper and accountant. He made his pen by connecting it to a barrel of ink with a rubber hose.

The Famous Idaho Potato (Idaho): Less folklore than industry observation, the Idaho potato is the best-selling potato in the United States.

Coronado (California): Francisco Vazquez de Coronado searched for the Seven Cities of Gold in the 1500s, a quest that took him from Mexico to California and even to Kansas. Though he never found the seven cities, his efforts made him famous.

The Celebrated Jumping Frog (California): The frog was immortalized in Mark Twain's story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," which became notable as a fable about gambling (and a very impressive amphibian).

Mormons (Utah): Why include Mormons on a map about folklore? It probably reflects the epic migration to Utah and the hardships suffered in the process. Mormons' identification with the state continues today, but it was probably even stronger in 1946, when the map was made.

John A. Sutter (California): Born in 1803, Sutter became symbolic of the California Gold Rush, and later established a fort that would become Sacramento.

Gold Rush (California): The catalyst for much of the settling and exploration of California, the 1840s Gold Rush captured the nation's attention and spurred Western migration (and the American imagination).

What the map means

The map of folklore shows the state of the American imagination (and Gropper's fascinations) in 1946. Notable gaps include the Pacific Northwest and the two future states of Hawaii and Alaska. Some inclusions — like Old Black Joe and Mormons — make for an unusual fit for modern eyes. But overall, it shows the iconic figures — real and fictional — that shaped the American imagination in the '40s and continue to do so today.

___________________________________________________________________

Thank you for sharing this! It's truly amazing!

ReplyDeleteIt's interesting you should post this. I'm sitting here looking up at my schedule of posts for the month and I see I have a "Fantasy Literature Rewind" about Carl Sandburg's Rootabaga Stories scheduled for next week. I'll have to remember some of the bits you said in this post when I start writing that. I plan on writing pieces about the works of L. Frank Baum (Oz tales and beyond) and Frank Stockton at some point in the future too. One thing I would like to remind people is that the word "fairy tale" was basically synonymous with "fanciful story for children" during the times when those men were writing. So, their tales don't necessarily follow the same form as the old European folk tales do.

ReplyDeleteOops. Meant to post this on the other post.

DeleteI totally agree that people confused fairy tales with 'fanciful stories for children' - both writers and readers, so we have a ton of those (wonderful) stories too, (the eighties seemed particularly prolific for this as well as the turn of the 20th C) but it's not what people 'thought' were fairy tales, that I'm interested in, but the closest thing to whatever definition we agree on is a fairy tale. You see, all around the world it's not too difficult to find fairy tales that are non-European (Indian, Arabic, Caribbean, Mexican, Japanese, Singaporean etc). Some of them overlap with folktales (like often - but not always - in Africa) but there are distinct non-European fairy tales found everywhere that still fit the definition . In the US, however, it's a more difficult thing to nut out. I think this country has the most amazing collections of literary 'American' fairy tales (thanks to writers like Jane Yolen, just for starters), but these generally haven't been circulating like fairy tales have tended to do in other countries. Some of it, I think, is because America is so young and oral storytelling was quickly superseded by print, periodicals and radio but it's not just that. The regional tales I mention DO fit the definition of fairy tale - it just doesn't seem to hold true for the country as a whole.

DeleteI'm curious to see what your librarian-extraordinaire research skills uncover in your investigation. I know this subject is slightly touchy for American folklorists but I think they're important questions. See, I do believe there are American fairy tales. I think we're just not great at recognizing them - yet.

PS I didn't realize Howard Pyle was American until I wrote my other post. I've loved The Wonder Clock for years but I do think it's more a European-influenced version of tales rather than 'real American' ones (whatever that means - I think it has yet to be properly defined).

I do find a certain 'type' of American immigrant tales (that have that element of Wonder) to be very fairy tale-like though - and they're uniquely American with mixed heritage flavors. Those, apart from the mountain and bayou tales, are probably my favorites, with their unique signature of 'otherland-American (eg Korean-American, Italian-American, Polish-American, Jewish-American etc). There's also that 'breed' of urban legend in America (not always scary) that skirts the fairy tale definition too - especially with regard to those children tell each other. I'd really like to see someone tracking these down and noting their importance.

PPS Adam, would it be possible to duplicate your reply over on the other post (and I'll do the same with this one in reply to that) so when people come across this in future they can see the discussion? (And add to it, if they're so inclined).

Looking forward to your Sandburg, Baum and Stockton posts!

You see, I tend to be ultra-inclusive in what I use. That's a post for another time, too. Something about the quirks of language and why I choose to include all that I do. Anyway, the US is a young country and our history isn't so far away. We're also a country that came into its own through industrialization. So, we tend to be more awash in legends, tall tales and ghost stories than fairy stories of the sort you're thinking of. Even then, our folklore is influenced by elements that other folk traditions aren't. For example, many of the legends about characters like Calamity Jane and Wild Bill Hickock were spread not by word of mouth but by newspapers (back in a time when news from far out west was kind of "stretchy" in terms of accuracy) and dime novels. Heck, Deadwood Dick was created exclusively for dime novels but for years many were convinced he actually existed.

DeleteOh, and yeah, I'll just copy and paste it.

I've read over the comments a few times but I'm still not sure what you're referring to with regard to being 'ultra-inclusive'. Curious to know what you mean..

DeleteRe the tall tales, ghost stories and legends - Australia has a lot of the same thing, and for the same reason, including the wild stories in the papers that people believed were real. [See? We're not completely different. ;) ] It's only recently that people are now looking to see where the fairy tales in Australia were and are - and they *are* finding them; both Australian versions of popular tale types found round the world, as well as 'original' ones. It just wasn't immediately obvious and it's opened a whole new and interesting branch of study that's ultimately different from the rest of our stories, though they are often related as well.

It would make sense that America - which is older than Australia, though not by much - would have some of the same challenges with regard to fairy tale identification.